COVID-19 has impacted the health or financial situations of millions of Americans, and it will have long-term consequences for retirement and financial planning.

For people unfortunate enough to have been hospitalized due to the virus, medical bills can be significant – especially if those patients must pay for out-of-network services, according to Dr. Carolyn McClanahan.

But that might be just the beginning, especially for people whose health was marginal prior to contracting COVID-19, said McClanahan, who in addition to her work as a medical doctor has a financial planning practice.

“[If] you’re older, you’re more likely to end up on a ventilator. The current death rate, if you end up on a ventilator is somewhere between 50% and 80%,” she said during a webcast hosted by The American College on Thursday. But for those who recover, “you lose the ability to walk, to take care of yourself. So most of those people need extended care.”

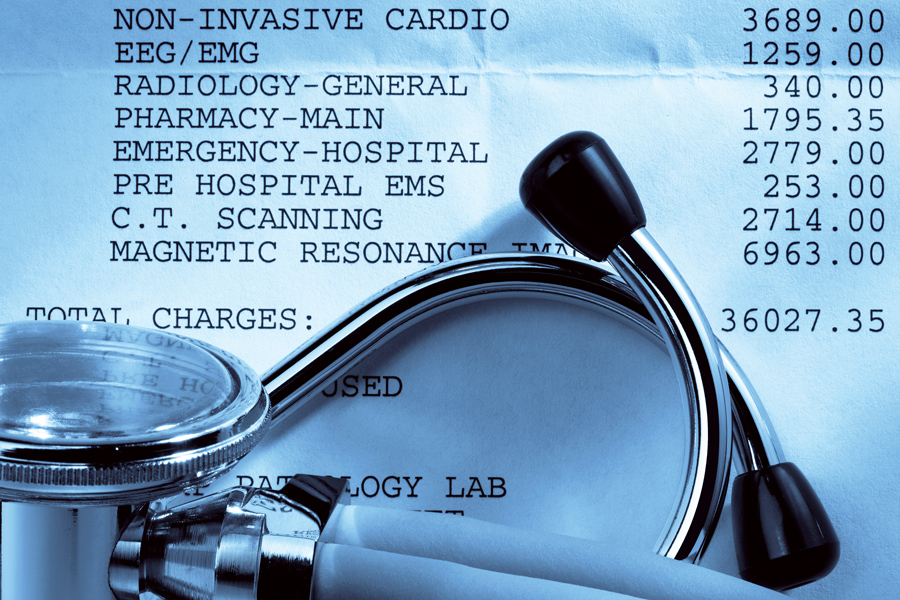

The initial treatment varies widely in cost. Without major complications, hospitalization related to COVID-19 could cost patients and their employer plans less than $10,000, according to a March study by the Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. But complications jack up the bill to an average of more than $20,000, according to the report, which based prices on 2018 hospitalization costs for pneumonia treatment. Being placed on a ventilator dramatically increases costs, with 96 hours of ventilator treatment resulting in a median bill of more than $88,000, according to the report.

A bout with COVID-19 can be “the seminal event” that leads to long-term care, McClanahan said.

Medicare pays for the first 100 days of in-home skilled nursing care, but for some that will not be enough, she said.

The pandemic should prompt financial planners, if they haven’t done so already, to discuss advance directives with clients, McClanahan said. Without documentation, some patients end up receiving much more treatment than they would have liked, and that can also saddle their adult children with debt, she noted.

“You always have to talk about what is important to you about quality of life,” she said. “If you have a serious illness, it’s really important to talk about your advance directives.”

One client who has amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease, told McClanahan he still has enjoyment in his life. “He said, ‘I’m still drinking my wine. If I get coronavirus, it’s not a bad way to go.’”

Even clients who are in good health should talk about long-term care, she said. For those who will lead very long lives, dementia can be common, which means living independently will be a challenge, she said.

“Almost everybody says, ‘I want to live in my home, no matter what,’” McClanahan said. But because of the cost of in-home care, “if you tell your children you never want to go to a nursing home, you’re hamstringing them with a huge long-term care bill.”

Although people tend to taper their spending in retirement, medical costs are an exception, said David Blanchett, head of retirement research for Morningstar’s Investment Management group.

“Most people don’t normally increase their consumption every year by [the rate of] inflation,” Blanchett said during the webcast. “Your spending tends to decrease in real dollars … But you have health care shocks.”

Clients should always have a long-term care plan, which can include self-insuring with their own assets or using products such as long-term care insurance, McClanahan said. Those insurance products are not her first choice, however, as it is impossible to know what long-term care will look like in the future, she said. For example, “warehousing” people in nursing homes could become less common, given the outsize risk it poses to those populations, as the pandemic has shown.

Financial planning includes an emergency fund, she said. But the total amount that people need to save for retirement should be based on an estimate of what their annual costs will be, rather than targeting a total amount of savings and then spending accordingly, she said.

This crisis is also showing the importance for near retirees to be invested conservatively, given the overall decline in the stock market this year, she said. The immense surge in unemployment claims also highlights the need for unemployment insurance, though some clients who are in their 50s or 60s and have ample savings might not need it, she noted.

This can also be a time for advisers to talk with clients about other insurance products, she said.

“As people reach their 70s and 80s, and they look like they’re going to have longevity, that’s when we look at immediate fixed annuities,” she said.

Driven by robust transaction activity amid market turbulence and increased focus on billion-dollar plus targets, Echelon Partners expects another all-time high in 2025.

The looming threat of federal funding cuts to state and local governments has lawmakers weighing a levy that was phased out in 1981.

The fintech firms' new tools and integrations address pain points in overseeing investment lineups, account monitoring, and more.

Canadian stocks are on a roll in 2025 as the country prepares to name a new Prime Minister.

Carson is expanding one of its relationships in Florida while Lido Advisors adds an $870 million practice in Silicon Valley.

RIAs face rising regulatory pressure in 2025. Forward-looking firms are responding with embedded technology, not more paperwork.

As inheritances are set to reshape client portfolios and next-gen heirs demand digital-first experiences, firms are retooling their wealth tech stacks and succession models in real time.