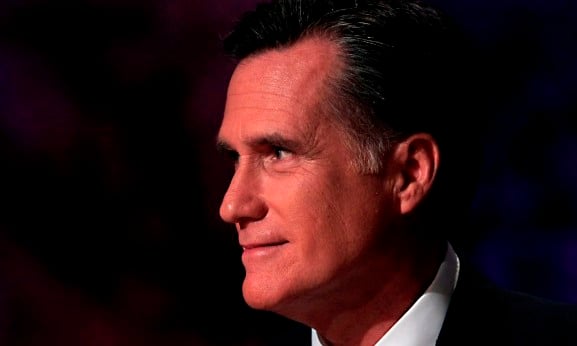

For all the attention devoted to Mitt Romney's tax returns last month, one element went largely unnoticed: They directly refute the Republican candidate's argument that higher tax rates deter capital investment.

Simply put, all of the investments made by

Bain Capital LLC, the private-equity company Romney cofounded in 1984 and ran until 1999, occurred when capital-gains rates were much higher than they are today. Yet Bain consistently attracted massive amounts of private capital, and thrived.

Bain's haul is further evidence that fair tax rates don't hold back profit-seeking capitalists, at least until those rates reach a point that no one is proposing. From 1984 until 1999, the top rates on capital gains -- the profit from investments as opposed to compensation for work -- were often at 28 percent, and never lower than 20 percent. Indeed, in 1987, under President Ronald Reagan, the 20 percent rate rose to 28 percent -- a 40 percent increase in potential taxation of Bain investment profit. (Yes, Reagan did raise taxes, even on capital.)

An analysis by the Wall Street Journal of 77 Bain deals in that time period showed that the firm “produced about $2.5 billion in gains for its investors,” on about $1.1 billion invested. Clearly, even with capital-gains rates almost double those today, fund managers such as Romney didn't lack investors.

No Deterrent

Others can debate whether the private-equity crucible created more jobs than it destroyed. One thing is certain, though: Investors signing up for a chance to earn, say, a gross $10 million profit on a deal weren't deterred by the prospect that taxes meant they would only keep a net $7.2 million.

Potential taxes were certainly disclosed to investors, and figured into the expected rate of return. And individual investors might have had offsets, such as the carried-forward losses from other deals reflected in the Romney tax return.

Particularly remarkable is the windfall Romney received from steep reductions in the capital-gains rate that took place after most of the deals he oversaw had closed. In 1997, the rate was cut to 20 percent, from 28 percent. It was reduced to the current 15 percent in 2003.

No one investing in a private-equity deal in 1990 could possibly say they anticipated the rate would be only 15 percent on profit still being paid out in 2010. Applying the reduced rate to deals previously closed couldn't possibly be viewed as an incentive to investors.

At the same time, because these rate cuts were applied retroactively, the Romney family enjoyed a windfall of about $600,000 each year in lower taxes paid (assuming the Romneys received the same $12 million in income from carried interest and other capital-gains returns since 2001 as they did in 2010).

When multiplied by thousands of similarly situated taxpayers, this after-the-fact tax-cut windfall contributed significantly to the budget deficit, even though its value to the economy remains dubious, as numerous analysts of capital- gains rate cuts have concluded.

At a time of ballooning federal deficits and frayed social safety nets, higher capital-gains rates can contribute meaningfully to deficit reduction and to helping a middle class that is struggling to stay afloat, without hampering good investments in American businesses.

The Romney tax returns vividly illustrate that fair tax rates don't deter those whom Republicans now routinely call “job creators” from investing.

As Warren Buffett so aptly put it, “I have worked with investors for 60 years and I have yet to see anyone -- not even when capital-gains rates were 39.9 percent in 1976-77 -- shy away from a sensible investment because of the tax rate on the potential gain.”

Conservative commentators will continue to recite their credo that letting the lower Bush-era tax cuts on capital gains expire -- and returning to the pre-2001 percent rate of 20 percent -- would kill investment and jobs. It will be hard for them to ignore the window provided by Romney's returns into the real world of private-equity investing and the economy.

--Bloomberg News--

(

David M. Abromowitz is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress Action Fund. The opinions expressed are his own.)